MEKDESE HAILE

On Lekso & The Experience of Grief in Life & Cinema

FEBruary 12, 2026 - INTERVIEW BY SARAH ONTIVEROS

"LEKSO (ልቅሶ): to mourn. a period of collective mourning including wailing, food, and fellowship to honor someone who has passed away. traditionally 40 days of wearing black and gathering. then again for the year anniversary, for no longer than 7 years."

Tell me about yourself in relation to the story you’ve told.

Okay, well, I'm first generation Ethiopian American, born and raised in Southwest Houston/Sugarland, Texas. And I'm really fascinated with death and the portrayal of it. Especially since it's one of the most common, inevitable, things that will happen in life. But I guess, as I got older, I was thinking about grief and thinking about how as a culture, how Ethiopians grieve, mourn, and handle death - I don't want to say it’s insane, but the traditions are so odd. And then I started thinking about the beautiful ways that we show up for one another, but also the contradictions and then I started thinking about the shock.

So how Ethiopians and Eritreans grieve - when someone dies you show up at their house and you cry, you wail, and it's loud and it's dramatic and growing up it's never really taught or explained, you just witness it, and there's so much death. And as a kid you just don't know what you're about to walk into, and my mom would be like, "okay, we're only going to be here for a few minutes” and then you walk in, and it’s like, what is going on?! But, again, it was never taught to us. And so I started wondering, is this fake? Is this acting? You know? And I originally wrote a feature script and it revolves around two childhood friends who spend 40 days of Lekso together (typically you sit for 40 days) and their relationship kind of rekindles, and the story is really dark, and it deals with mental illness, it deals with culture and all that stuff…And so I was like, what if I take the adults of the world of my feature and make them kids and talk about the first time this kid experiences death because yeah, it's shocking, it's new.

I also added this layer of doubt. The person who dies is the person that kind of discipled her and introduced faith to her. It's a grandma and granddaughter. And so I wanted to tell a story about someone that thinks she can heal and doesn't. At the end of the day my whole premise is that death is inevitable. God is ultimately in control or, you know, if you don't believe in God, a higher power… And I think a lot of people, even as somebody who's 35, I deal with doubt, and I think that doubt is normal, but I do think that there is this feeling of betrayal or wonder that causes you to either lose faith or question it, and I just wanted to explore those feelings of death and doubt and be true to the culture.

I really like that you went with the kids as opposed to adults because as an outsider looking in, I think we are kind of at that same age level in our minds about the culture and the tradition, [Lekso] was something that I had never heard of before. So it was interesting to read about a lot of what the tradition is and see the amount of grief that someone is able to hold in their body and then to be able to express that in a ceremonial way and in a familial environment. It's kind of refreshing in a way too, as an American we're kind of told not to do those things. We're very much meant to hide our feelings and our emotions, and maybe not meant to, but that's just something that's kind of the norm, we cry behind closed doors.

The thing is though, I wanted to show the contrast of life. A lot of our shots are beautiful and bright because we're in the kid's perspective and it's like you're kind of sheltered from it. And by sheltered I mean you're exposed to it but you're not encouraged to participate. And it's almost like opposite messaging where it's like the adults can express loudly and just release; where kids are kind of told, “don't cry” or “don't be sad.” And we're not a monolith so I'm sure there were some parents that talked to their kids [about Lekso]. Not mine and not a lot of my friends.

Why do you think that is? As far as kids not being encouraged to partake. Is the grief only supposed to be held within the Lekso ceremony? Within that time after death - is it more preserved for that?

Yeah, for me, at no age, was I ever really encouraged to cry. Even at a funeral, the consoling is pretty opposite. But the adults, from the outside looking in, it looks like this spectacle. You're like, oh! And I was even very protective about some of the images because there's not a lot of photography or videography of a Lekso and the only images I really found were from this Ethiopian Airlines plane crash that happened years ago. And so it's not something that's really documented. And then the pictures that I have are blurry and they're very much fantastical, like they're exaggerated.

And I don't know, “that could really sell the project” is the feedback I got. And I even had one professor say, “can you do the sound?” … It is a very unique kind of sound that we just grew up with, but the plan was to have no audio and just the motion. And I only wanted it shot from the second floor looking down. She’s upstairs, so we're getting a POV from up there. But [the wailing] is present! And I don't want to spoil this but it's surreal and what you actually see is from overhead. So yeah, everybody loved it. The crew/cast responded really well to it because it is shocking. But to me, this is a sound that is associated with so much death.

“But what is a tasteful way to show culture? Because people love trauma. And hopefully when you watch the film you see so much life, and so much culture, so much of the joy in the midst of it.”

Yeah, it seems like there's a lot of nuance there, like as a ceremony or tradition to be a part of, but also to be a spectator of as well. At first when you were saying you didn't necessarily want the wailing, I was thinking it was more out of a protective nature, like you wanted to protect that tradition and have it be something that's sacred.

The protective part I am, I don't want to exploit wailing and grief in our tradition to sell a project. But what is a tasteful way to show culture? Because people love trauma. And hopefully when you watch the film you see so much life, and so much culture, so much of the joy in the midst of it.

I love that. Speaking on the trauma thing. I just watched the movie Hamnet. Have you seen it? It was so intense, and I found myself looking away at certain moments because it just felt so vulnerable and private, like I shouldn’t be there.

Yes! And I knew what was gonna happen. When the brother was taking it in, like what it means to be a protector. Oh my gosh. And the dad was kind of proud of him, which was also devastating. But yeah, there's a lot of things that I liked about it, but I remember being in the theater like, “let it out, do more!”

And that's kind of why I wanted to bring it up because I've been reading a lot of things that have been circulating about it since it’s come out - about grief and how we are meant to feel those things. We're meant to express them in a very raw way, it's not something we're meant to hold on to, it's meant to be expelled. It doesn't matter what that looks like. And when I was reading about Lekso and the tradition of it, there were a lot of similarities there as far as wanting to expel grief. They want it to be something they can hand off to the world and their community, and I love that it's over consecutive days because I read somewhere that it’s so the pain doesn't try to settle in.

Yeah it’s 40 days. Six months, and then like every year for seven years. My mom and my grandma wore black for seven years and you wear black, sometimes you cut your hair. And the difficult part is you can't show happiness or joy, or like you've moved on - it's almost disrespectful to. Which is also a complicated feeling. I think being in the States it’s like you get two/three days off of work, maybe. And there's just not a deep reverence for grief... I mean, with my culture, it's unheard of to not show up at certain things. But it's different out here in the States.

Yeah, that was one of the questions I wanted to ask. How did shooting this in Houston or having it based in Houston, shape the narrative of the story?

Well, I really wanted it to be in Houston because I'm from here, and I think it’s important to show the diaspora… you know the beauty of Houston... The story takes place in two locations, they're both in the Southwest and down the street from the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. Which is like the religion that these characters are primarily. And yeah, there wasn't a non-Ethiopian character. So it's interesting because it felt very Houston to me, but it is also a different Houston.

I’m sure that feels very authentic to the story too.

Okay, there was one non-Ethiopian haha my friend, but she looks it, so I told her to come!

But growing up in the South, we're in the Bible belt so faith is almost indoctrinated in all things, politics, school. And being Ethiopian Orthodox, I always felt a little bit like an outsider. And I had so many dreams for how I wanted to capture everything. But of course, budget takes all. And I broke down every scene because I was telling a loss of faith / loss of innocence story. And I rated every scene, one through five, as far as importance and I shared it with my team. And it was like, if we have to lose a scene, it's this. And we did have to lose it. It was the one scene that was like a cooking montage, which I loved, but I didn't know how to shoot a cooking montage that didn't feel like The Bear… But food is a huge part of our culture too. Even feeding somebody out of your hands is cultural. That's what we grew up with at these Leksos. And I was searching Shot Deck and I was searching all these things. And I was like, is that common? Is it not? And I was actually really excited to learn how intimate that is and how our culture is very hospitable. So even if we didn’t get how to prepare the food, you see how we eat together. And the coffee ceremony, we have that and you see what it's like. The fellowship and the gathering is there. It may be a little dark. The mood may be different, but the gathering is still there, we're still eating and drinking together.

There was something I read in your pitch deck that said food, or I guess the act of eating, almost becomes a character. And I really love that you made that distinction because it is such a big part of a lot of cultures.

Which was also why that scene of the cooking montage was really hard because I was like, “what's in this dish? Okay, what do you do with it?” And it was like, are the recipes gonna die with my parents? And my mom always says it's not too late to learn.

Having made this film and having to do a bit of research for it, do you feel more connected to your culture?

I think it showed me, unfortunately, how American I am. I exist in the world where people are like, what are you? Are you this? And most of the time, they don't know what I am. They'll think I'm Indian, they'll think I'm Somalian. I've always been other here. But we grew up very pan- African, very, like, we are Black, we are Ethiopian. And with so much pride. So I didn't care. Honestly, I didn't care. But the majority of my life I'm talked to in a different language - I live at home. The majority of my life was in church, which is also two languages. There's the church language, and then there's the Ethiopian language, there's every May and June - a million graduation's, weddings. People die often, where at these gatherings, it's like, every week I'm eating Ethiopian. I'm so exposed to it that I didn't realize that being first generation was so deep, I have a Southern accent at times, like when I'm really talking loud. I love southern culture. I love that immersion. And that's what I want to talk about. I want to talk about my experience as a first gen. I'm not qualified to talk about Ethiopian stories. That's not my story.

I think that was kind of one of my last lingering questions. What are some of the things you want to accomplish with the film? I know you were saying your family didn’t necessarily want to do it because it seemed like something that was taboo.

My family, yes, the community needed some persuading.

But I like that they still showed up and were very professional because I think, not just you but your culture and people in your community want y'all’s stories to be told. I think a lot of people feel that way and they may not be the ones to do it, but if there’s someone who can and is willing and is going to do it authentically, I think they want to show up and show out for someone and something like that.

You know, I was just happy that they were there. They were, I think, so hard on themselves. But, I think your question was what do I want from this?

Yeah, what do you hope to accomplish?

All right, I got a bunch of answers… So, I will say, it was very challenging in comparison to doing like five films in two years and that was with resources [in LA]. And being here, I thought I could still live here and be a filmmaker here. And it's very challenging to see that the industry is not really built for that here. And I feel like there are so many, not just talented people, but so many important stories, because Houston is so diverse. The two filmmakers I can name from Houston are two white men. And outside of their identity there are stories, there's culture. I went to the most diverse high school in my district. University of Houston was like second in the nation. And I went to LA and LA is very diverse. And it just really shows me, Hollywood aside, who gets to tell stories… If I didn't have my producer, and if they didn't believe in the story and take reduced rates…they took a risk and it was just like, everything was an act of faith. And I'm educated, I am privileged to some extent to where I can forgo rent money to do this. But what about all the people that can’t? Are we saying that only privileged people with money and resources can be storytellers? It's an accessibility issue.

Yeah, artists should be able to create. I think the accessibility issue is the main problem here. There's not many avenues for any of us to create on the level that we want to create.

Yeah. And working with Bryce [Saucier] really elevated the project too. I wanted Bryce and his team to have what they wanted to tell the story. That access to resources that makes things elevated are important too…

But, where do I want this film to go? It is technically a film in progress. Yes, I do want it to reach the masses. I do want it to be in festivals. But at the end of the day, I have my core audience and then I have people that I feel like would learn, appreciate, etcetera. But I also made this film as a gift to my culture… And everything is about impact, not numbers.

Yes. And I think the way that you went about it, wanting the finer things, it’s a reflection of your artistry. Especially if you want it to be a feature film. If you want to tell stories on that scale, I think how you approach them, what tools you use, and what people you collaborate with - that's all part of that, that encapsulates cinema.

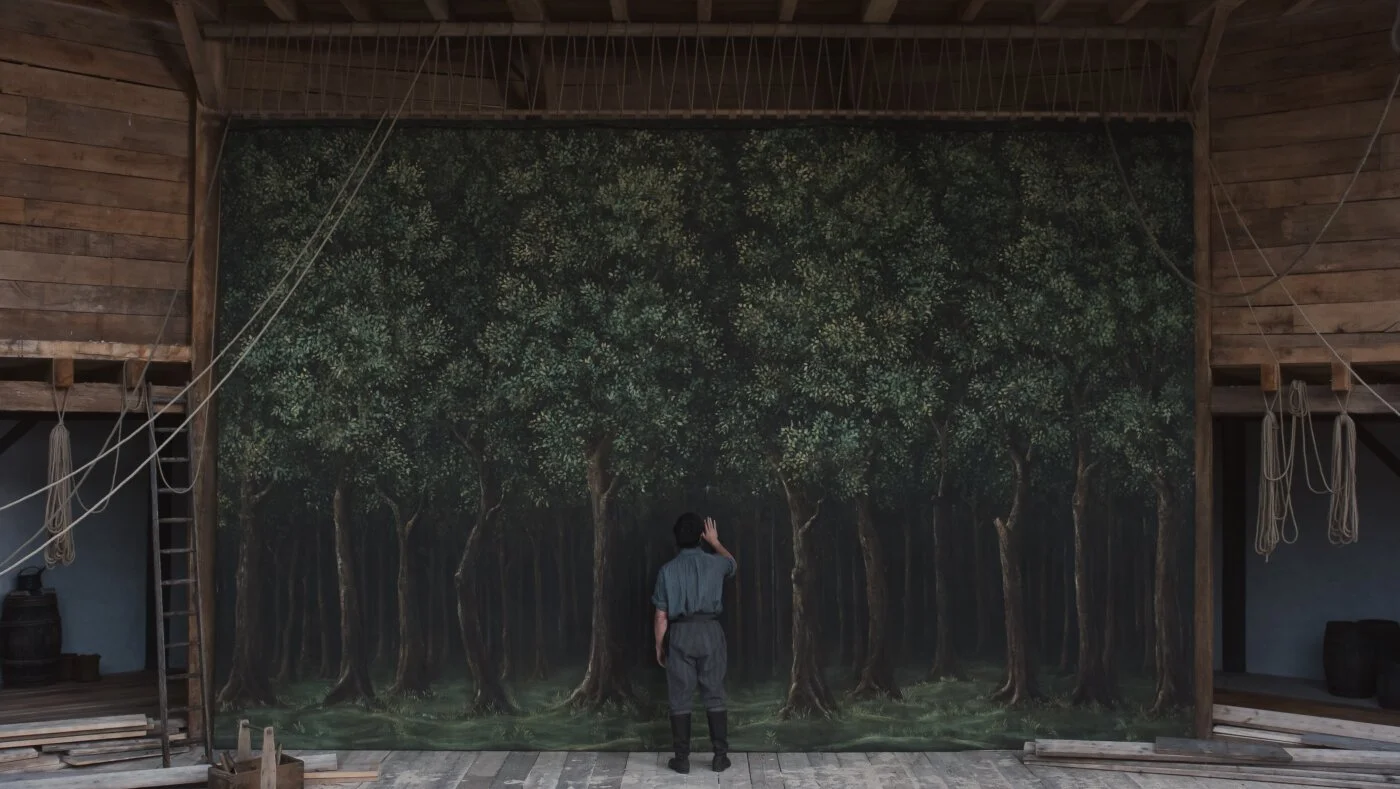

Yes. And then I think [Bryce] also knew what I wanted from each scene to where he kind of encouraged things… Like, “we should do it like this.” And anything with the wailing, he was great at checking in. And then our final scene, I struggled a lot with it, like our last, last shot. And I'm not gonna give it away, but he was a huge part in helping me communicate the feeling that I wanted, which was risky in that it was borderline disrespectful to the faith. But I'm telling a loss of faith story. I'm telling the loss of innocence story. But the girl's also a kid, you know, her faith journey doesn't die there. So it was like, how do we communicate that visually? And it's why I'm so grateful for our collaboration.

That’s all of it…everything that we do in this industry, it's all collaboration. And when it's with the right people…it's magic.

Haile and her team are currently crowdfunding for post-production - to support you can visit their campaign page and leave a monetary donation or share the link.

You can find Haile and follow along on Instagram @mekdesehaile